Witajcie! Już dawno miałem opisać ten menadżer okien dla systemów Linux i BSD. Według danych na dzień dzisiejszy jest on najlżejszym dostępnym. Przedstawie dwa zastowania dla niego.

Podzieliłem tekst na 3 części:

- Cześć 1- TinyWM jako kiosk internetowy [1]

- Cześć 2 - TinyWM jako panel administratora [2]

- Podsumowanie [3]

Część 1

[15] [9] [4]

Kod źródłowy

Oczywiście nie będę wszystkiego opisywał, bo nie oto chodzi. Cały kod źródłowy to 50 linijek w języku C. Mniej już się nie da. Wersja 1.3 wygląda tak:

/* TinyWM is written by Nick Welch , 2005.

*

* This software is in the public domain

* and is provided AS IS, with NO WARRANTY. */

/* much of tinywm's purpose is to serve as a very basic example of how to do X

* stuff and/or understand window managers, so i wanted to put comments in the

* code explaining things, but i really hate wading through code that is

* over-commented -- and for that matter, tinywm is supposed to be as concise

* as possible, so having lots of comments just wasn't really fitting for it.

* i want tinywm.c to be something you can just look at and go "wow, that's

* it? cool!" so what i did was just copy it over to annotated.c and comment

* the hell out of it. ahh, but now i have to make every code change twice!

* oh well. i could always use some sort of script to process the comments out

* of this and write it to tinywm.c ... nah.

*/

/* most X stuff will be included with Xlib.h, but a few things require other

* headers, like Xmd.h, keysym.h, etc.

*/

#include

#define MAX(a, b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b))

int main()

{

Display * dpy;

Window root;

XWindowAttributes attr;

/* we use this to save the pointer's state at the beginning of the

* move/resize.

*/

XButtonEvent start;

XEvent ev;

/* return failure status if we can't connect */

if(!(dpy = XOpenDisplay(0x0))) return 1;

/* you'll usually be referencing the root window a lot. this is a somewhat

* naive approach that will only work on the default screen. most people

* only have one screen, but not everyone. if you run multi-head without

* xinerama then you quite possibly have multiple screens. (i'm not sure

* about vendor-specific implementations, like nvidia's)

*

* many, probably most window managers only handle one screen, so in

* reality this isn't really *that* naive.

*

* if you wanted to get the root window of a specific screen you'd use

* RootWindow(), but the user can also control which screen is our default:

* if they set $DISPLAY to ":0.foo", then our default screen number is

* whatever they specify "foo" as.

*/

root = DefaultRootWindow(dpy);

/* you could also include keysym.h and use the XK_F1 constant instead of

* the call to XStringToKeysym, but this method is more "dynamic." imagine

* you have config files which specify key bindings. instead of parsing

* the key names and having a huge table or whatever to map strings to XK_*

* constants, you can just take the user-specified string and hand it off

* to XStringToKeysym. XStringToKeysym will give you back the appropriate

* keysym or tell you if it's an invalid key name.

*

* a keysym is basically a platform-independent numeric representation of a

* key, like "F1", "a", "b", "L", "5", "Shift", etc. a keycode is a

* numeric representation of a key on the keyboard sent by the keyboard

* driver (or something along those lines -- i'm no hardware/driver expert)

* to X. so we never want to hard-code keycodes, because they can and will

* differ between systems.

*/

XGrabKey(dpy, XKeysymToKeycode(dpy, XStringToKeysym("F1")), Mod1Mask, root,

True, GrabModeAsync, GrabModeAsync);

/* XGrabKey and XGrabButton are basically ways of saying "when this

* combination of modifiers and key/button is pressed, send me the events."

* so we can safely assume that we'll receive Alt+F1 events, Alt+Button1

* events, and Alt+Button3 events, but no others. You can either do

* individual grabs like these for key/mouse combinations, or you can use

* XSelectInput with KeyPressMask/ButtonPressMask/etc to catch all events

* of those types and filter them as you receive them.

*/

XGrabButton(dpy, 1, Mod1Mask, root, True, ButtonPressMask, GrabModeAsync,

GrabModeAsync, None, None);

XGrabButton(dpy, 3, Mod1Mask, root, True, ButtonPressMask, GrabModeAsync,

GrabModeAsync, None, None);

for(;;)

{

/* this is the most basic way of looping through X events; you can be

* more flexible by using XPending(), or ConnectionNumber() along with

* select() (or poll() or whatever floats your boat).

*/

XNextEvent(dpy, &ev);

/* this is our keybinding for raising windows. as i saw someone

* mention on the ratpoison wiki, it is pretty stupid; however, i

* wanted to fit some sort of keyboard binding in here somewhere, and

* this was the best fit for it.

*

* i was a little confused about .window vs. .subwindow for a while,

* but a little RTFMing took care of that. our passive grabs above

* grabbed on the root window, so since we're only interested in events

* for its child windows, we look at .subwindow. when subwindow

* None, that means that the window the event happened in was the same

* window that was grabbed on -- in this case, the root window.

*/

if(ev.type == KeyPress && ev.xkey.subwindow != None)

XRaiseWindow(dpy, ev.xkey.subwindow);

else if(ev.type == ButtonPress && ev.xbutton.subwindow != None)

{

/* now we take command of the pointer, looking for motion and

* button release events.

*/

XGrabPointer(dpy, ev.xbutton.subwindow, True,

PointerMotionMask|ButtonReleaseMask, GrabModeAsync,

GrabModeAsync, None, None, CurrentTime);

/* we "remember" the position of the pointer at the beginning of

* our move/resize, and the size/position of the window. that way,

* when the pointer moves, we can compare it to our initial data

* and move/resize accordingly.

*/

XGetWindowAttributes(dpy, ev.xbutton.subwindow, &attr);

start = ev.xbutton;

}

/* the only way we'd receive a motion notify event is if we already did

* a pointer grab and we're in move/resize mode, so we assume that. */

else if(ev.type == MotionNotify)

{

int xdiff, ydiff;

/* here we "compress" motion notify events. if there are 10 of

* them waiting, it makes no sense to look at any of them but the

* most recent. in some cases -- if the window is really big or

* things are just acting slowly in general -- failing to do this

* can result in a lot of "drag lag."

*

* for window managers with things like desktop switching, it can

* also be useful to compress EnterNotify events, so that you don't

* get "focus flicker" as windows shuffle around underneath the

* pointer.

*/

while(XCheckTypedEvent(dpy, MotionNotify, &ev));

/* now we use the stuff we saved at the beginning of the

* move/resize and compare it to the pointer's current position to

* determine what the window's new size or position should be.

*

* if the initial button press was button 1, then we're moving.

* otherwise it was 3 and we're resizing.

*

* we also make sure not to go negative with the window's

* dimensions, resulting in "wrapping" which will make our window

* something ridiculous like 65000 pixels wide (often accompanied

* by lots of swapping and slowdown).

*

* even worse is if we get "lucky" and hit a width or height of

* exactly zero, triggering an X error. so we specify a minimum

* width/height of 1 pixel.

*/

xdiff = ev.xbutton.x_root - start.x_root;

ydiff = ev.xbutton.y_root - start.y_root;

XMoveResizeWindow(dpy, ev.xmotion.window,

attr.x + (start.button==1 ? xdiff : 0),

attr.y + (start.button==1 ? ydiff : 0),

MAX(1, attr.width + (start.button==3 ? xdiff : 0)),

MAX(1, attr.height + (start.button==3 ? ydiff : 0)));

}

/* like motion notifies, the only way we'll receive a button release is

* during a move/resize, due to our pointer grab. this ends the

* move/resize.

*/

else if(ev.type == ButtonRelease)

XUngrabPointer(dpy, CurrentTime);

}

}

Większość w powyższym kodzie to opisy w języku angielskim do poszczególnych sekcji, dlatego wydaje się on dłuższy.

Praktyczne zastosowanie - kiosk internetowy

Normalnych praktycznych zastosowań dla tego menadżera właściwie nie ma. (pewnie się zastanawiasz po co w ogóle ja to pisze) Jednym, które ma jakiś sens jest zastosowanie w kiosku internetowym, profesjonalnie zwanym kiosk mode. Jest to sama przeglądarka internetowa udostępniona użytkownikom końcowym.

Jako system bazowy posłużę się Debianem w wersji 6.0 beta 1. Obraz instalacyjny systemu w wersji 32 bitowej dostępny tutaj. Jako przeglądarkę internetową wykorzystam midori w wersji 0.2.9 pochodzącą z repozytorium Hadreta [5].

Oczywiście większość dystrybucji zawiera opisywany menadżer w swoich repozytoriach, wybrałem Debiana bo jego obraz instalacyjny miałem pod ręką.

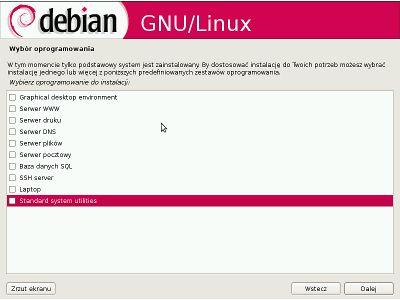

Instalujemy system klikając dalej, dalej itd. Wybieramy tylko system podstawowy, czyli na tym ekranie nie wybieramy nic.

[6]

[6]

Po zainstalowaniu systemu logujemy się na użytkownika root i instalujemy następujące paczki: apt-get install xorg tinywm midori

Jeśli ktoś chce nowsze midori musi dodać następujące repozytorium:

nano /etc/apt/sources.list

i dodać to:

deb http://hadret.rootnode.net/debian/ unstable main

(zapisuje się ctrl +x ) oraz wykonać polecenie wyżej. Po zainstalowaniu wylogowujemy się z roota i logujemy na użytkownika końcowego i wykonać polecenie:

nano ~/.xinitrc

i wkleić: * jeśli tylko zobaczyć jak działa sam menadżer:

xsetroot -solid black &

xterm &

tinywm

od razu z przeglądarką

xsetroot -solid black & xterm & midori & tinywm

W pierwszym przypadku wygląda to tak:

zaś w drugim:

Zmieniamy rozmiar przeglądarki i działa.

Część 2

[15] [9] [4]

TinyWM jako panel administratora

O ile system Windows Server ciężko się zarządza przez tryb tekstowy, to w systemach uniksowych jest prostsze. Pomimo tego wiele osób, które zaczynają swoją przygodę z administrowaniem serwerów pracujących pod kontrolą systemów Linux/BSD ma problem. Chciałyby najlepiej wszystko "wyklikać". W związku z tym, że im mniej zainstalowanych rzeczy w systemie serwerowym, tym bezpieczniej i wydajniej. Tutaj przedstawiane środowisko idealnie pasuje. Do prezentacji możliwości posłużę, że się systemem Debian Squezee (6.0) w wersji 32 bitowej działający na platformie XEN [10] działającej na serwerze Dell R710.

Przygotowanie środowiska do pracy

Podobnie jak w przypadku web kiosku potrzebujemy X Window System i menadżer okien oraz serwera pulpitu zdalnego (vnc). Ten ostatni tylko w wypadku zdalnej konfiguracji.

apt-get install xorg xserver-xorg tinywm x11vnc

Konfiguracja pakietu x11vnc jest dostępna tutaj. Na przeszkodzie nie stoi również wykorzystanie jako serwera pulpitu zdalnego aplikacji NoMachine NX [11].

Również wykorzystuję następujące pakiety:

apt-get install feh htop irssi pcmanfm rxvt-unicode gmrun

- feh - jako menadżer tapety, by ładnie wyglądało

- htop - rozwinięta wersja programu top, menadżer zadań/uruchomionych procesów

- irrsi - klient sieci irc (zrzut 2)

- pcmanfm - lekki menadżer plików

- rxvt-unicode - w skrócie zwany urxvt - terminal

- gmrun - starter programów

Panel informujący administratora

Konfiguracja pliku .xinitrc:

feh --bg-scale ~/Debian_Grass_by_hadret.jpg &

urxvt -g 80x24+0+0 &

urxvt -g 80x24+0+0 &

gmrun &

tinywm

Ta konfiguracja uruchamia 2 terminale, które można przesunąć kombinacją klawiszy "lewy alt + lewy klawisz myszy" oraz starter programów.

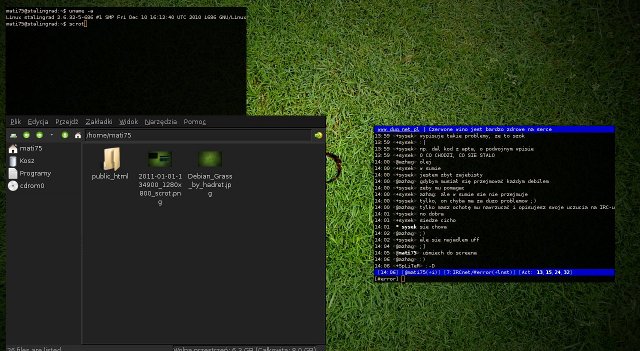

Tak to wygląda w działaniu:

W terminalu została uruchomiona aplikacja htop.

Panel zarządzania plikami

Zauważyłem mało osób lubi korzystać z konsolowej aplikacji do zarządzania plikami mc. Wolą jednak klikać. Więc można również w takim przypadku wykorzystać menadżer TinyWM.

Konfiguracja pliku .xinitrc:

feh --bg-scale ~/Debian_Grass_by_hadret.jpg &

urxvt -g 80x24+0+0 &

pcmanfm &

gmrun &

tinywm

W tym przypadku wykorzystałem również aplikację lxappearance:

apt-get install lxappearance

aby dostosować wygląd menadżera, bo po standardowej instalacji za ładnie nie wygląda. Wykorzystałem do tego styl: Drakfire Black [13] oraz ikony nuoveXT.2.2.

Wygląda to tak:

W terminalu została uruchomiona aplikacja irssi, służąca do komunikacji za pomocą sieci irc. W tym przypadku czysto dla rozrywki.

Podsumowanie

[15] [9] [4]

Myślę, że w zupełności zaprezentowałem możliwości tego malutkiego środowiska. Jeśli ma ktoś jakiś pomysł pisać, spróbuje zaprezentować. W niniejszej prezentacji wykorzystałem tapetę Debian Grass autorstwa Hadreta [16].

Pozdrawiam serdecznie!